Thursday, November 11, 2010

It's Raining Two and a Half Men

When you go to see a Todd Phillips movie, you have a pretty good idea what you're getting yourself into. Anyone who's seen Road Trip, Old School, or The Hangover can probably see the similarities that run through all the director's films. Booze and drugs, women, partying, and some far-off destination that the heroes of the film need to get to by tomorrow or else everything will fall apart! The tone is always goofy and as over the top as things get, they never stray too far from fun territory.

That's what makes his newest flick, Due Date, such a surprising experience. It contains all the ingredients of his previous films (which, let's be honest, he's ripped off from the comedies of others from decades ago), but the tone of this film is considerably darker than his previous films. As funny as the movie is, there is a subtle undercurrent of something more melancholy and substantial than anything we've seen in his wacky buddy comedies of the past 10 years. The puzzling thing is that, although this heavier tone is clearly there, I can't quite put my finger on where it's coming from.

Part of it might be the fact that he's working with only two principal characters in this film, whereas in previous films he usually had a larger ensemble of at least three actors. When you've got a group of actors on screen, like The Marx Brothers or The Three Stooges, it lends itself to broader, more situation-driven comedy. But with only two characters, it's necessary to dig a little deeper. Due Date depends on the interpersonal relationships of two seriously flawed characters with issues that they haven't got a clue how to deal with: Peter (Robert Downey, Jr.) is about to become a father, and Ethan (Zach Galifianakis) has just lost his.

I think it's this more introspective approach that made me enjoy Due Date more than Phillips' previous films. I'm what feels like one of the few people who didn't drool all over The Hangover last year. I enjoyed the film, but I certainly wasn't among the many of my friends who raved that it was the funniest film they'd ever seen. The massive success it has endured baffles me to a certain extent. I think The Hangover's biggest strength is that, unlike most broad comedies, it's not predictable. It's still rigidly formulaic and doesn't take many risks, but the antics that the characters endure are nearly impossible to see coming, unlike comedies of the same commercial caliber over the past few years, like the incredibly overrated Wedding Crashers.

Although Due Date is more formulaic in terms of plot, it took me emotionally to places I didn't expect to go. So often in comedies, the emotional heart of the movie is reduced to an insincere romantic sub-plot, usually so the creators have some excuse to justify all the dick jokes they've been making for the last ninety minutes. This bothers me on a number of levels, one of which is that no one should need an excuse for any kind of joke; but mainly, insincere emotion in movies annoys the hell out of me. The Hangover didn't even try to add any emotion, sincere or otherwise, but the pain the characters deal with in Due Date is sincere and very real; Ethan's delusional desire to become an actor, and inability to deal with the death of his father, and Peter's many character flaws, aren't there as excess baggage, but are honest depictions. Phillips is interested in them and cares about them.

To a certain extent, I wanted the film to deal with this more than it did. Peter, nor the film itself, ever seem to address the evident fact that he is not at all ready to be a father. He is prone to intense outbursts of anger; at one point he physically harms a child simply because he doesn't have the patience to deal with the kid. He doesn't even have the patience to live with Ethan's dog for a few days.

One thing I found particularly troubling was the frequent depiction of Robert Downey, Jr. using drugs. No one else in the theatre seemed to react to this, but I surely can't be the only one that remembers that, before his recent comeback, Downey was most famous for his crippling drug problems. I'm glad that things have turned around for him, since he is a fantastic actor and deserves the recognition he is now receiving. But seeing him tossing handfuls of Vicodin into his mouth left an awful pit in my stomach. Was the line, "I've never done drugs in my life," intended to be ironic? I know a film should be able to view its character as separate from the performer, but I still found this troubling. Maybe viewed ten years from now the film wouldn't have this same effect, but it wasn't that long ago that the most famous image of Downey was not in an iron suit but in an orange jump suit.

Another thing that bugged me was how the many scene-stealing actors in the supporting cast were so underused. Juliette Lewis, Danny McBride, and RZA are great, but their appearances are basically reduced to cameos, and they could have been utilized so much more. (The last time I saw RZA on film was in Funny People last year, where he wore a goofy deli worker's uniform. Here he's in a security guards uniform. What is it that's so funny about seeing the RZA in uniform? The appeal is weirdly strong).

These flaws aside, the movie is still hilarious and clever. Like I said earlier though, its greatest strength is in its emotional sincerity that is so often absent from Phillips' movies and other comedies like them. It was a refreshing viewing and wasn't at all the Hangover retread I expected. Even though this follows the particular plot formula of a buddy comedy, this movie has another layer to it that sets it apart from the others in the pack.

Saturday, November 6, 2010

Bring On the Dancing Girls: Who's That Knocking at My Door

While studying film at NYU under professor Haig Manoogian, a young Martin Scorsese penned a planned trilogy of semi-autobiographical screenplays that chronicled the coming of age of a young Italian-American man growing up in New York's lower east side. The first script, titled Jerusalem, Jerusalem, followed the central character as a teenager studying in a seminary to become a priest. The second, Bring On the Dancing Girls, dealt with the conflict between his Catholic views and sexual realities. And the third, Season of the Witch, depicted his initiation into the lower echelons of the mafia in Little Italy.

Bring On the Dancing Girls began production as a short student film at NYU, eventually expanding into a feature, Scorsese's first. It was originally screened with the title I Call First at the Chicago Film Fest in 1967, but it was theatrically released with the title Who's That Knocking at My Door in 1969.

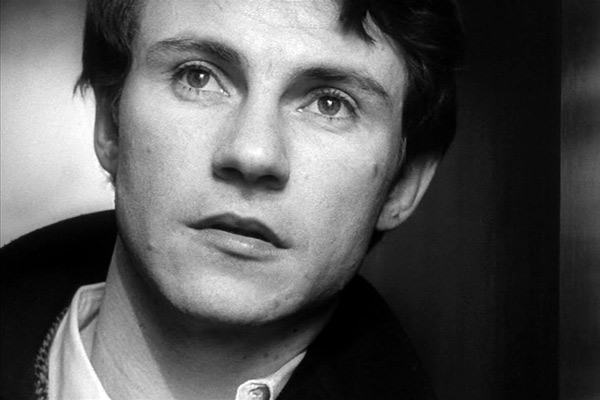

The film deals with Catholic guilt perhaps more explicitly than any of Scorsese's subsequent features. The young protagonist, J.R (Harvey Keitel in his first film role)., is a typical young guy living in New York's Little Italy, spending his weekend nights cruising around with his group of friends, killing time by drinking, shooting the shit, seeing movies, trying to get laid. He's young, smart, and hopelessly bored.

A strong sense of everyday, mundane boredom pervades the film. We get the strong sense that J.R.'s nights out with his friends are painfully routine, and that he has perhaps lived the same night many nights over. This makes it all the more important when J.R. meets a beautiful, unnamed young woman (Zina Bethune) on the ferry. The two make a connection in their conversations about John Wayne movies. The two begin seeing each other and J.R. falls desperately in love.

The extend of J.R.'s affection is apparent in his treatment of "the girl" as compared to how he and his friends treat other women in their sexual exploits. In one scene at a party, him and his friends interact with two girls whom they have never met before. The girls have clearly been invited to the party for the purpose of sex, and nothing else. J.R. and his friends view the women as sexual objects, present only to be used to fulfill the desires of the young men.

By comparison, J.R. views Bethune's character as an almost angelic figure. He idealizes her to an extreme degree and places her on a pedestal high above all other girls. He declines to engage in sexual activity with her, which he so readily pursues with other girls he does not hold in the same esteem.

It is through these relationships that J.R.'s skewed views on sex and on women become clear. The forbidden, Catholic view of sex that has been drilled into J.R. manifests itself intensely in these interactions. He views sex as a sin, and women who practice it are therefore tainted. J.R. can never view the girls at the party as women worthy of his affection. They are, through their sins, lesser than him. On the other hand, Bethune's character is an unreachable goddess. J.R. can't bring himself to make love to her because, by doing so, he will taint her through her own sexuality.

On paper, the problems of this sexist viewpoint are apparent. However, these problems manifest themselves for J.R. when "the girl" confesses to him that she is not a virgin; she was raped by the last boy she was romantically involved with. J.R.'s view of her is instantly poisoned with this news, and he walks away from the conversation, unable to cope.

It is at this point that the issues of conflict and guilt truly begin to plague J.R. He is able to see how his feelings and beliefs contradict the logic of the situation; he loves the girl, but his image of her that lead him to love her has been destroyed. Although she is logically innocent, she is still theologically impure.

His complex highlights not just the problems of just this particular relationship, but of J.R.'s romantic aspirations as a whole. J.R.'s views result in his complete inability to achieve romantic happiness to any degree; he can never be with a woman he considers below him, but he also can't have any woman he deems worthy, because once he does have her, he himself spoils her.

What makes the film particularly brilliant is that it chooses not to condemn J.R.'s obviously sexist beliefs, but rather forces the audience to identify with them. The film does not condone the beliefs either; it makes it explicitly clear that the girl is not a bad person but a smart, independent, and capable girl who was, tragically, the victim of a brutal crime. J.R., too, is able to see this from a logical standpoint, but is unable to reconcile this logic with his belief system.

The film doesn't demonize or endorse Catholicism or sexism, but rather explores the emotional landscape that results from the conflict between belief and emotion, logic and faith, teaching and experience. It is clear that Scorsese sympathizes with the female character, and sees J.R.'s dismissal of her as repugnant. But this is J.R.'s film, and although the film allows the viewer to pass judgment on the character rather than doing so itself.

In fact, a strong sense of Catholic identity is apparent throughout the film. Catholic imagery can be found in every nook and cranny of this movie. The fantasy sequence in which J.R. is tied to the bed makes Keitel look uncannily like a crucified Christ. Religious icons fill J.R.'s home, and we get the sense that, even when he is not explicitly dealing with religion, his religious identity manifests itself in every aspect of his life. The film's final scene, in which J.R. cuts his lip on a crucifix while kissing it, is a perfect piece of symbolism that illustrates the double-edged sword of J.R.'s religious identity, and how his church brings him both peace and pain.

Watching the film, one intrinsically gets the feeling that Scorsese truly understands this material. This film is the first example of dozens by Scorsese that deal with Catholic guilt, and the inability to reconcile one's Catholic beliefs and lessons with their experience of the world and their feelings towards it. J.R. doesn't think that the girl has done something wrong, but he believes it. The film is not for everyone, but for Scorsese fans and for people interested in the theme of Catholic guilt, or of dogma versus human experience, this film is a fantastically dark moral labyrinth.

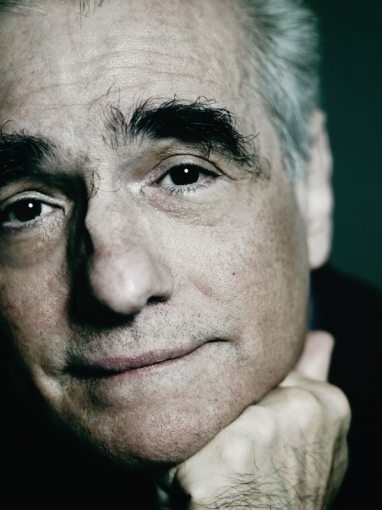

An Ordinary Parish Priest: The Scorsese Filmography

Over this past summer, I undertook the somewhat daunting task of viewing the entire feature filmography of my favourite living director, Martin Scorsese. I viewed the films chronologically by release date, and did this purely for my own enjoyment. I had been inspired to look at all the films after picking up a copy of Roger Ebert's fantastic book, Scorsese by Ebert. Being obsessed with movies, the thorough analysis that Ebert provided of Scorsese's career didn't quench the thirst I had for insight on Scorsese's works. Instead, it merely served as a jumping-off point for my curiosity about the great director, and I was compelled to watch all his films and do some writing of my own.

So, basically, I'm going to write a series of blog entries about his features. I'll probably post them in the order in which the films were released, although I might deviate. Also, I'll obviously post about other subjects, I'm not interested in just blogging about Marty.

Sadly, due to their absence from rental stores at the time of my binge, I was unable to view Kundun, his 1997 film about the Dalai Lama, or his 2008 Rolling Stones concert film, Shine a Light. However, hopefully I will have had the opportunity to view them by the time I reach them in his filmography. I might also write about some of his shorts or his documentary work, depending on how I'm feeling.

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

The Social Network: Humanity Versus Genius

As the year is nearing its end, I find myself giving in to that irresistible urge to start creating lists and naming the "best" films or records of the year. I know this is a silly undertaking, but then again, so are the Oscars, and I still find myself getting excited for them every year. Even though there's still a solid two months left in 2010 and there is still plenty of time for contenders to come out, I still find myself going over the films I've seen over the last ten months trying to find which ones stand out above the rest. Time and time again, I find myself drifting back towards David Fincher's The Social Network.

What I find so particularly intriguing about Fincher's film isn't the detailed outline of the founding of Facebook as a business entity (brilliantly scripted by The West Wing creator Aaron Sorkin), or even the supposed checkered past of the social networking website (the movie asserts that not only was the website spawned from a drunken act of misogyny, but also that the basic framework of the site was a stolen idea). What intrigues me most about The Social Network is its commentary on the nature of genius, and how that genius comes both as an asset and a crippling handicap.

The character of Mark Zuckerberg, played to perfection by Jesse Eisenberg, is one of the most intriguing movie anti-heroes in recent memory, and the more I dwell on him, the more I feel inclined to include him with Travis Bickle, Daniel Plainview, and Charles Foster Kane on the list of all-time great subjects of brilliant character pieces in film. Although the character Mark Zuckerberg probably bears little resemblance to the real Mark Zuckerberg, the character himself is far more interesting and fertile for analysis. Many will probably see The Social Network more as a social commentary or a sort of pseudo-historical film rather than a character piece. The film is all of these things, but its greatest strength lies in the character of Mark and the double-edged sword of his genius.

Although the film makes no attempt to make Mark seem likable or relatable, there is no question about the fact that the film certainly regards him as a genius. We see his natural inclination to computer programming, and it becomes clear that although he is not the most well-known or well-loved on the Harvard campus, his technical wizardry is unparalleled. Mark things and breathes in code. When he his dumped by his girlfriend, his retaliation doesn't come in words or physical actions, but in HTML.

However, the careful viewer will see that, in order for Mark to gain this upper hand in his mental capacity for programming, he also has to lose something. Mark's superior understanding of computer language comes at the cost of his ability to connect with anyone on a human level. His obsession with computer coding, and eventually with Facebook, send him into a sort of mental tunnel vision that make him cold towards other people, unable to relate or empathize with anyone else. The film is rife with examples of this: the first thing we see is Mark being dumped by his girlfriend, and we can hardly blame her. His prickish and insensitive personality is apparent from his first lines. Throughout the movie, Mark betrays and manipulates business partners, friends, and allies left and right, but he doesn't seem to do these things out of mean spirit or even selfishness. On the contrary, when Mark is confronted by those he has wronged, he usually seems unable to understand why they are angry with him.

Mark's shortcoming comes from this inability to understand other people; in order to understand computer language so thoroughly, his understanding of humanity is sacrificed. This is evident not just in his interpersonal relationships, but in his social relationships as a whole. Mark desperately wants to be accepted into one of the Harvard final clubs or fraternities, but despite his intelligence, he remains a nobody. His failure to do so manifests itself as a deep resentment of the system that rejected him. His creation of Facebook, and the many "fuck yous" he throws out along the way, seem to be retaliation towards the entire social world that has rejected him. However, his longing to join this world persists despite his projected hatred; when his best friend Eduardo is accepted to an exclusive final club, Mark's jealousy is clear. When Eduardo claims that Mark betrayed him just to get back at him for making it into the final club, there isn't much to make the audience think that this isn't the case.

The film doesn't even seem to regard Mark as entirely human; we see many times throughout the film that he seems to be impervious to the cold, and when other characters are painfully freezing, he doesn't even seem to notice the temperature. He walks through thick snow in casual clothing and doesn't seem to notice. He rejects food every time he is offered it, and we almost never see him eating, save for at the end of the film when we see a sliver of humanity peak through as he connects with a young law intern played by the always wonderful Rashida Jones. The things that most people are sensitive to, Mark is unable to recognize, and these physical oddities serve to symbolize his emotional ones.

And therein lies the brilliance of The Social Network's depiction of the dual nature of genius. Mark longs to become a part of the social in-crowd, but despite all his success, never succeeds in doing so, not because he won't, but because he can't. The handicap of his genius, despite opening seemingly infinite doors for him, will never open the only door he wants to go through. The financial and commercial successes he achieves do not satisfy his loneliness, as we see at the end of the film as he gazes longingly at his ex's Facebook profile. He wants nothing more than to be accepted, and when he finds he is incapable of achieving this, he strikes back with a relentless ambition that drives him to zealotry and near madness.

We see how the other characters fall victim to emotional plights as they climb the ladder of success. Eduardo is torn apart by his rocky relationships with his best friend and insane girlfriend, and Sean Parker (in a surprisingly effective performance by Justin Timberlake) spirals into a lifestyle of sex and drug abuse, but Mark never falls victim to the vices of their world, because he can never be a part of it.

In his review of The Social Network, Roger Ebert wisely compares the character of Mark Zuckerberg to the real life figure of Bobby Fischer. Their similarities are uncanny: Fischer, a childhood chess prodigy who was arguably the greatest player that ever lived, found himself a victim of his own inability to apply to human connection the same virtuosic touch he applied to the game of chess. Fischer became increasingly bizarre, openly speaking about his belief in conspiracy theories that the Jewish people were a secret evil organization that controlled the world (Fischer was himself Jewish), and he died an exile in Scandinavia, a sad genius ignored by his home country as a shadow of what he once was. His brilliance gave way to an arrogance that was both his greatest success and his undoing, much like Mark Zuckerberg.

It is sometimes theorized that genius itself is not an increased mental capacity in an individual, but rather a slightly skewed perspective from which the subject views the world. This is certainly the case with Mark Zuckerberg, who is able to see the world through the eyes of a computer but not through the eyes of a human being. It is in the exploration of Mark's genius that the film finds its own genius.

What I find so particularly intriguing about Fincher's film isn't the detailed outline of the founding of Facebook as a business entity (brilliantly scripted by The West Wing creator Aaron Sorkin), or even the supposed checkered past of the social networking website (the movie asserts that not only was the website spawned from a drunken act of misogyny, but also that the basic framework of the site was a stolen idea). What intrigues me most about The Social Network is its commentary on the nature of genius, and how that genius comes both as an asset and a crippling handicap.

The character of Mark Zuckerberg, played to perfection by Jesse Eisenberg, is one of the most intriguing movie anti-heroes in recent memory, and the more I dwell on him, the more I feel inclined to include him with Travis Bickle, Daniel Plainview, and Charles Foster Kane on the list of all-time great subjects of brilliant character pieces in film. Although the character Mark Zuckerberg probably bears little resemblance to the real Mark Zuckerberg, the character himself is far more interesting and fertile for analysis. Many will probably see The Social Network more as a social commentary or a sort of pseudo-historical film rather than a character piece. The film is all of these things, but its greatest strength lies in the character of Mark and the double-edged sword of his genius.

Although the film makes no attempt to make Mark seem likable or relatable, there is no question about the fact that the film certainly regards him as a genius. We see his natural inclination to computer programming, and it becomes clear that although he is not the most well-known or well-loved on the Harvard campus, his technical wizardry is unparalleled. Mark things and breathes in code. When he his dumped by his girlfriend, his retaliation doesn't come in words or physical actions, but in HTML.

However, the careful viewer will see that, in order for Mark to gain this upper hand in his mental capacity for programming, he also has to lose something. Mark's superior understanding of computer language comes at the cost of his ability to connect with anyone on a human level. His obsession with computer coding, and eventually with Facebook, send him into a sort of mental tunnel vision that make him cold towards other people, unable to relate or empathize with anyone else. The film is rife with examples of this: the first thing we see is Mark being dumped by his girlfriend, and we can hardly blame her. His prickish and insensitive personality is apparent from his first lines. Throughout the movie, Mark betrays and manipulates business partners, friends, and allies left and right, but he doesn't seem to do these things out of mean spirit or even selfishness. On the contrary, when Mark is confronted by those he has wronged, he usually seems unable to understand why they are angry with him.

Mark's shortcoming comes from this inability to understand other people; in order to understand computer language so thoroughly, his understanding of humanity is sacrificed. This is evident not just in his interpersonal relationships, but in his social relationships as a whole. Mark desperately wants to be accepted into one of the Harvard final clubs or fraternities, but despite his intelligence, he remains a nobody. His failure to do so manifests itself as a deep resentment of the system that rejected him. His creation of Facebook, and the many "fuck yous" he throws out along the way, seem to be retaliation towards the entire social world that has rejected him. However, his longing to join this world persists despite his projected hatred; when his best friend Eduardo is accepted to an exclusive final club, Mark's jealousy is clear. When Eduardo claims that Mark betrayed him just to get back at him for making it into the final club, there isn't much to make the audience think that this isn't the case.

The film doesn't even seem to regard Mark as entirely human; we see many times throughout the film that he seems to be impervious to the cold, and when other characters are painfully freezing, he doesn't even seem to notice the temperature. He walks through thick snow in casual clothing and doesn't seem to notice. He rejects food every time he is offered it, and we almost never see him eating, save for at the end of the film when we see a sliver of humanity peak through as he connects with a young law intern played by the always wonderful Rashida Jones. The things that most people are sensitive to, Mark is unable to recognize, and these physical oddities serve to symbolize his emotional ones.

And therein lies the brilliance of The Social Network's depiction of the dual nature of genius. Mark longs to become a part of the social in-crowd, but despite all his success, never succeeds in doing so, not because he won't, but because he can't. The handicap of his genius, despite opening seemingly infinite doors for him, will never open the only door he wants to go through. The financial and commercial successes he achieves do not satisfy his loneliness, as we see at the end of the film as he gazes longingly at his ex's Facebook profile. He wants nothing more than to be accepted, and when he finds he is incapable of achieving this, he strikes back with a relentless ambition that drives him to zealotry and near madness.

We see how the other characters fall victim to emotional plights as they climb the ladder of success. Eduardo is torn apart by his rocky relationships with his best friend and insane girlfriend, and Sean Parker (in a surprisingly effective performance by Justin Timberlake) spirals into a lifestyle of sex and drug abuse, but Mark never falls victim to the vices of their world, because he can never be a part of it.

In his review of The Social Network, Roger Ebert wisely compares the character of Mark Zuckerberg to the real life figure of Bobby Fischer. Their similarities are uncanny: Fischer, a childhood chess prodigy who was arguably the greatest player that ever lived, found himself a victim of his own inability to apply to human connection the same virtuosic touch he applied to the game of chess. Fischer became increasingly bizarre, openly speaking about his belief in conspiracy theories that the Jewish people were a secret evil organization that controlled the world (Fischer was himself Jewish), and he died an exile in Scandinavia, a sad genius ignored by his home country as a shadow of what he once was. His brilliance gave way to an arrogance that was both his greatest success and his undoing, much like Mark Zuckerberg.

It is sometimes theorized that genius itself is not an increased mental capacity in an individual, but rather a slightly skewed perspective from which the subject views the world. This is certainly the case with Mark Zuckerberg, who is able to see the world through the eyes of a computer but not through the eyes of a human being. It is in the exploration of Mark's genius that the film finds its own genius.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)