Shark Still Looks Fake

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Steve Jobs: R. iPeace

The impact and influence of the life of Steve Jobs can not be over estimated. Not only did he change the face of technology, commercialism, and capitalism as we know it, he has along with Bill Gates fundamentally changed the way human beings live and coexist on this planet in the 20th and 21st centuries. The influence of computer technology on our personal lives today would have been unheard of a mere thirty years ago. It will likely be decades, perhaps even centuries, before we can fully perceive the wide reach of his influence. He will likely stand in history next to William Randolph Hearst, Alexander Graham Bell, and Henry Ford on the shortlist of individuals who have had the greatest impact on our daily lives, for better or for worse.

Wednesday, April 6, 2011

You Don't Pass Through Fire to Get to Heaven

I decided to upload a couple of my old film class essays. This is one I did last year on Judd Apatow's Funny People.

Judd Apatow’s film Funny People questions why comedians are, in Apatow’s opinion, generally unhappy people. The film centres on two comedians, a veteran stand-up comedian and comedy movie star named George Simmons (Adam Sandler) who has been diagnosed with terminal leukemia, and a young aspiring stand-up comedian named Ira Wright (Seth Rogen). The film portrays life as a comedian through these two characters and their relationship with one another, with Ira serving as George’s hired assistant and writer, while George acts as a sort of mentor to Ira. It is through these characters, and the many other comedians in their lives, that Apatow explores the idea of comedians as unhappy individuals.

The film ultimately views comedy and the use of humour as a defence mechanism used by people to cope with their unhappiness, and that the people who excel in comedy are able to do so because of the pain they experience. Humour is viewed as something that comes to people who are already unhappy; comedy is a reaction to their unhappiness. The topics and themes of the comedy produced by the characters in the film have their origins in the things that make them unhappy. The notion of comedy as a reaction to unhappiness is demonstrated in Funny People through the comedy of George, Ira, and the other comedians around them, as well as the way the characters themselves act in real life when they are not performing comedy. Ultimately, Apatow presents comedy as a way of coping with and distancing oneself from unhappiness.

The stand-up comedy of the characters in the film is related to the same things they are unhappy about. The characters themselves may not be entirely aware of this, but it is clear that the things that inspire them to write comedy are the same things that make them unhappy. Ira’s stand-up material illustrates this very well. Many of his jokes are direct reflections of his own insecurity. He is not confident in his relationships with women, and as a result, much of his comedy is about his inability to successfully pursue romantic relationships with women. Many of his jokes also make reference to his own perception of himself as being romantically and sexually unattractive. He calls himself down in a way by constantly referencing his own habits that are somewhat looked down upon by the general public, like masturbation and flatulence. His comedic persona that he has developed in his routine is a reflection of how he sees himself, and this self-image is not a flattering one. His seemingly playful self-deprecating humour ultimately paints a darker portrait of a deeply insecure young man who is unhappy and lacking self-confidence. This is an insecurity that permeates Ira’s life much more deeply than he hints at in his act, and it affects him in more ways than just his relationships with women. Ira is deeply insecure about himself as a comedian; he has a great passion for comedy, but he is not as successful as he would like to be. At the beginning of the film, he is still not being paid for performing his act, and audiences do not seem to be responding positively to his material. This pain is strengthened by the sense of competition felt amongst Ira and his roommates, Leo Koenig (Jonah Hill) and Mark Taylor Jackson (Jason Schwartzman), both of whom are having considerably more success in their careers than him. Later in the film, it is revealed that Ira’s insecurity reaches back to childhood, when he was ridiculed and embarrassed by the mispronunciation of his birth surname, Weiner (actually pronounced “whiner” as opposed to the common misnomer “weener”). Ira’s embarrassment over his surname was so profound that he was actually driven to change his name to Wright. He also discusses his parents’ divorce and their hateful relationship with one another. Ira suggests that he may feel a certain degree of guilt about his parents’ divorce, or that he perhaps feels devalued in the eyes of his parents by the experience, when he says to George, “My mom thinks that my dad is the devil; I’m not sure what that makes me, technically.” Although he makes the statement like an offhand joke, it is extremely revealing about Ira and how he views himself. When Ira tells his childhood stories to George, George hints that these are likely what drove Ira to become a comedian in the first place.

George has issues from childhood that also make appearances in his comedy. He tells many jokes about his troubled relationship with his father. The jokes are often about his father showing obvious dislike for George. In reality, George speaks a great deal off-stage about his relationship with his father. George feels he is a disappointment to his father and that his father doesn’t respect him as a comedian or as a man. George also hints that his father may have been abusive. Although Apatow briefly shows a sort of reconciliation between George and his father, the scene appears in a montage where George is attempting to reconnect with people in his life before he succumbs to his illness; despite the seeming heartfelt and sincere reconciliation that George has with his father, the other events in the montage show George unable to reconnect with a lot of people, many of whom are comedians who are too self-involved to really sympathize with George. At the end of the montage, George expresses a great deal of regret for the way things have turned out when he says to Ira, “I played it all wrong.” The montage, and the scenes following it, also deals with his regret over the dissolution of his relationship with his former fiancée, Laura (Leslie Mann). George wishes that their relationship had never ended and that the two were still together. This desire manifests itself in George’s stand-up, when he makes frequent reference to his single life, the “one that got away”, and the fact that he does not have children. In one very telling stand-up routine, he jokes about his married friends who encourage him to pursue a romantic relationship, whereas he would sooner spend his life with his riches and material wealth. This reflects one of the central factors of George’s depression; he is an immensely wealthy person, but his wealth brings him no happiness and he is ultimately alone. As the home video that opens the film illustrates, George was much happier as a young man when, even as a poor and struggling comedian, he still had meaningful friendships and relationships with other people. George also tells many jokes about aging and death, which is an obvious reflection of his fears about his illness and impending death. One other important element he jokes about that is essential to understanding George’s character is his lack of belief in God. In his time of struggle, he feels utterly alone because he has absolutely no one to turn to, no faith or positive philosophy to comfort him.

Outside of George and Ira’s stand-up, there are instances in which both characters use humour to cope with unhappiness or intense emotions. One such scene takes place when Laura comes to visit George after learning that he is dying. When Laura confesses to George that he was the love of her life, she grasps his hand, in tears. George then makes a joke about her large hands, saying, “They always made my penis look small.” Although she laughs at the joke and he somewhat cheers her up, the joke is very telling about George. When sharing this incredibly emotional and intimate moment with Laura, he is unable to deal with the intimacy of the moment and makes the joke because it is the only way he can lessen its impact. A similar event takes place when Dr. Lars (Torsten Voges) gives George and Ira the news that George’s condition is worsening. George proceeds to jokingly mock Lars for his accent, telling him that it makes him seem scary. Even when Lars makes his discomfort about the jokes obvious, George continues to berate him with jokes, and Ira even joins in a little. This seems like a strange time for George to begin telling jokes, but he is unable to react any other way; the severity of the moment is so intense that George can only respond with humour, because it is his only weapon against his suffering. The same is true of Ira in this situation. Ira also hides behind humour when he is attempting to ask Daisy Danby (Aubrey Plaza) out on a date and embarrasses himself.

The film views unhappiness not just as a potential cause for comedy, but as an essential ingredient to it. Comedy’s dependence on unhappiness is illustrated through characters like Mark Taylor Jackson and Randy Springs (Aziz Ansari). These characters are the most successful of the small-time comedians in the film; audiences respond well to Randy’s stand-up, and Mark is the star of a sitcom on NBC titled Yo, Teach! for which he is paid $25,000 a week. Randy and Mark, when compared to Ira as peers, are considerably happier and more confident than Ira. They are enjoying their success and are optimistic about their direction in life. However, the comedy produced by these characters is not of the same calibre as that of visibly unhappier characters like Ira, George, Leo, and Daisy. Randy’s stand-up, while popular, is depicted as being somewhat witless, focusing more on his wacky behaviour than actual jokes or comedy. Mark’s sitcom is viewed by the other characters as being formulaic and uninventive, resorting to lowest-common-denominator sitcom structures rather than taking risks to be funny. Even though these characters are more successful and, ultimately, happier than the central characters, they are less talented as comedians because they do not experience the pain that Apatow views as necessary for understanding comedy.

Funny People’s main theme of comedy as a product of unhappiness ultimately views the pain suffered by the main characters as more than just an inspiration for their comedy, but as an ingredient essential to the genesis of all brave and meaningful humour. Even though the film ends on an optimistic note, the ending is modest and the neurosis and personal struggles of the characters are still present to the end. Even as their lives and careers are on an upswing, their improvement seems to come more from an acceptance of their mental and emotional states rather than a successful triumph over those feelings. Judd Apatow makes the theme of comedy’s essence of unhappiness resonate deeply with the stand-up comedy, contrast amongst characters, and character interactions that populate the film.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

From the Demented Mind of a Movie Freak

Recently I was driving from my home to the pharmacy to get a prescription filled. I live in the rural areas surrounding Winnipeg, about 15 minutes outside of the city limits, so I have a little bit of a drive before I reach any sign of civilization. On this drive, I noticed that I was the only person driving into the city. In fact, I couldn't see any cars in front of or behind me anywhere in the southbound lanes of the highway. The northbound lanes leading outside the city, however, had a long line of cars stretching to both ends of visibility.

Now, every time I witness this phenomenon, it makes me incredibly nervous. I'd never been able to figure out why, but from a pretty early age (probably seven) it always unsettled me. Now as a young adult, when I encounter the lonely lane I find myself frantically scanning the radio channels for news of some terrifying disaster that all in the city are fleeing, so as to ensure that I don't drive myself straight into the middle of it. I don't really have any logic to justify this paranoia, but it is present nevertheless. Any explanation always escaped me up until this last encounter, when the bizarre origin of the fear suddenly came to me.

A few hours before leaving for the pharmacy, I had flipped on the television to find that the movie Independence Day was playing on one of the twenty-four hour movie channels. I thought I'd turn it on, since I never miss the opportunity to see Will Smith's famous "Welcome to Earf" line. As I flicked on the channel, I saw the image of a massive traffic jam of cars trying to exit the city as the alien ship loomed over the Empire State Building. The lane going towards the city had only one vehicle, driven by Jeff Goldblum and Judd Hirsch. Hirsch looks at the traffic jam and bemuses, "Everyone's trying to get out of New York, we're the only schmucks trying to get in."

As I reached for my radio dial a couple of hours later in the car, I stopped. It all made sense now. My parents had bought me Independence Day on VHS when it was released on home video in 1997. I spent a good chunk of my childhood watching it. I spent most of my childhood watching movies. I was always obsessed with them, and the ones I owned got heavy rotation when I couldn't convince my mom to drive me to the video store to rent Spaceballs or The Incredible Journey.

And it was only then, as I realized what a profound effect that a way-too-literal interpretation of Independence Day had on me, that I began to contemplate how the movies I'd seen as a kid have shaped me into the person I am today.

When I think back on my earliest memories, many of them are of movies. I have a handful of very early memories, from way younger than most people can remember. I remember the birth of my sister, at which time I would have been 21 months old. I also remember my 2nd birthday a few months later, when my dad took me to see Sesame Street Live at the old Winnipeg arena. I have some very vague memories of the Muppets on stage, but what I remember most vividly is the bathroom at the old arena, with the gross trough urinal. After that, my earliest memory is my first trip to the movie theater.

It wasn't much longer after the Muppets show, since I was still two years old. My mom took me to see a re-release of Pinocchio at the theater in Garden City Mall. I'm not sure if it was my first time seeing the movie; we had a massive collection of Disney films on VHS that grew incrementally from my birth until the age of about eight. Pinocchio may have been in that collection before I saw it in the theater, but the experience had a huge impact on me. I remember the sheer enormity of the images on screen. In that theater that now seems so tiny, the tiny two-year-old me looked up at the towering screen and marveled at its size without any conception of how much that experience would influence my life. I wasn't overwhelmed by the giant images on screen; I was absorbed by them. What was happening on screen seemed to be the only thing in the world. They weren't just entropic images in a room with chairs and people and popcorn and a sticky floor. Those extra things weren't even there. There was just the movie, and it was magic.

A year or so later, when my sister turned two, my mom took us to see Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in the theater. The detail I remember most about that movie is how much it scared me. I remember Pinocchio being scary too. But when I look back on the movies I loved as a kid, especially in my first five years, the ones that have stuck with me and I still love today are the ones that scared the bejeesus out of me. A lot of those early Disney films are really horrifying. The little boys turning into donkeys in Pinocchio, the Queen ordering her huntsman to cut out Snow White's heart, the circus workers abusing the animals in Dumbo, and the cruel villains in The Rescuers are just a few examples of things that really made my stomach drop as a young child. Another big one was The Wizard of Oz. The movie has an otherworldly atmosphere, with the aged sepia and surreal Technicolor making the whole thing feel more like a dream then a movie. Plus, there are plenty of terrifying story points, like the Wicked Witch, the tornado, and the flying monkeys that really gave me goosebumps (and to be honest, still do).

Among the large collection of animated movies on VHS in my house, there was a small handful of live-action films that my parents had bought for themselves. The ones that I remember most vividly is Back to the Future. It is to this day my favourite movie of all time. We had the whole trilogy and I watched them endlessly. I don't know about you, but when I was a kid, I would find a movie I liked and watch it over and over again, every day, for weeks. Back to the Future easily got played the most out of any of the tapes in the house. When I say I have seen BTTF at least a hundred times, it isn't an exaggeration. If anything, it's a low estimate. There were months long periods where I would watch it every day, and those periods were many. Since falling out of the habit of daily viewings (later than most, at around age 12), I've always made a point of watching all three at least once a year, along with Lawrence of Arabia.

To this day, I have the entire movie memorized. Not just dialogue, but shots, music cues, everything. I can tell you the exact moment in Earth Angel (the scene starts at 0:21) that Alan Silvestri's score kicks in and drowns out the band playing the song, and the exact moment that the song swells back up again, and Silvestri's score syncs up with the band and the two pieces become one, the strings lifting the music of The Starlighters and Marvin Berry's vocals to a beautiful and triumphant crescendo. It's my favourite piece of film scoring ever. I don't know if I've ever seen a more effective use of music in a scene, and as cheesy and cliche as this sounds, every time I hear it I feel a warmth and comfort in my heart that almost nothing else in life gives me. When they parodied the scene on Family Guy and Brian sang Earth Angel, I actually cried while watching it, simply because it made me realize my love for that movie, and that scene in particular.

I feel like BTTF really had a profound influence on who I am. I looked up to the characters in that movie. I see a lot of myself in George and Marty McFly. Both characters have a creative endeavour (writing or music) that they excel in, but both lack the self confidence to carry out their dreams to pursue their creativity. Both are neurotic and unsure of themselves. I also feel a weird affinity to Doc Brown. I looked up to him so much as a kid. He was so smart and I admired his intelligence. It made me want to be as smart as he was, and made me push hard to do well in school, and to try and read and learn as much as I possibly could.

Every time I see the film, I genuinely feel like I'm seeing a part of my soul depicted on screen. I've seen movies since then, especially in my adult life, that have made me feel this too. I remember viewings of Raging Bull, Ferris Bueller's Day Off, and 2001: A Space Odyssey when I felt like the film I was watching was made especially for me. But no other film has persisted with me the way BTTF has. I've been watching it since I was born, and I only grow fonder of it as time grows on. Unlike so many movies I grew out of, BTTF gets better every time I watch it. So many other movies of that era seem dated. Their cheesy 80s synth soundtracks and teen romance feel contrived and untimely when experienced today. But Back to the Future is perfect. When Huey Lewis and the News come skipping onto the soundtrack, they absolutely belong there. When George and Lorraine kiss on the dance floor, it's real love.

I think it's for these reasons that film remains the most important creative force in my life. Even though I'm much more active in music, music is like a reflex to me. It's like breathing, I can't not do it. Even if I tried not to play music, I would instinctively pick up an instrument. But film is the rejuvenating art that constantly brings new thoughts and ideas and feelings into my life and inspires me to create. I thought I had discovered a new obsession in high school when I decided I wanted to go to film school after I graduated. But only now, in an incidental drive to the pharmacy, do I realize that film has always been the greatest source of happiness for me. And I hope it always will be.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

It's Raining Two and a Half Men

When you go to see a Todd Phillips movie, you have a pretty good idea what you're getting yourself into. Anyone who's seen Road Trip, Old School, or The Hangover can probably see the similarities that run through all the director's films. Booze and drugs, women, partying, and some far-off destination that the heroes of the film need to get to by tomorrow or else everything will fall apart! The tone is always goofy and as over the top as things get, they never stray too far from fun territory.

That's what makes his newest flick, Due Date, such a surprising experience. It contains all the ingredients of his previous films (which, let's be honest, he's ripped off from the comedies of others from decades ago), but the tone of this film is considerably darker than his previous films. As funny as the movie is, there is a subtle undercurrent of something more melancholy and substantial than anything we've seen in his wacky buddy comedies of the past 10 years. The puzzling thing is that, although this heavier tone is clearly there, I can't quite put my finger on where it's coming from.

Part of it might be the fact that he's working with only two principal characters in this film, whereas in previous films he usually had a larger ensemble of at least three actors. When you've got a group of actors on screen, like The Marx Brothers or The Three Stooges, it lends itself to broader, more situation-driven comedy. But with only two characters, it's necessary to dig a little deeper. Due Date depends on the interpersonal relationships of two seriously flawed characters with issues that they haven't got a clue how to deal with: Peter (Robert Downey, Jr.) is about to become a father, and Ethan (Zach Galifianakis) has just lost his.

I think it's this more introspective approach that made me enjoy Due Date more than Phillips' previous films. I'm what feels like one of the few people who didn't drool all over The Hangover last year. I enjoyed the film, but I certainly wasn't among the many of my friends who raved that it was the funniest film they'd ever seen. The massive success it has endured baffles me to a certain extent. I think The Hangover's biggest strength is that, unlike most broad comedies, it's not predictable. It's still rigidly formulaic and doesn't take many risks, but the antics that the characters endure are nearly impossible to see coming, unlike comedies of the same commercial caliber over the past few years, like the incredibly overrated Wedding Crashers.

Although Due Date is more formulaic in terms of plot, it took me emotionally to places I didn't expect to go. So often in comedies, the emotional heart of the movie is reduced to an insincere romantic sub-plot, usually so the creators have some excuse to justify all the dick jokes they've been making for the last ninety minutes. This bothers me on a number of levels, one of which is that no one should need an excuse for any kind of joke; but mainly, insincere emotion in movies annoys the hell out of me. The Hangover didn't even try to add any emotion, sincere or otherwise, but the pain the characters deal with in Due Date is sincere and very real; Ethan's delusional desire to become an actor, and inability to deal with the death of his father, and Peter's many character flaws, aren't there as excess baggage, but are honest depictions. Phillips is interested in them and cares about them.

To a certain extent, I wanted the film to deal with this more than it did. Peter, nor the film itself, ever seem to address the evident fact that he is not at all ready to be a father. He is prone to intense outbursts of anger; at one point he physically harms a child simply because he doesn't have the patience to deal with the kid. He doesn't even have the patience to live with Ethan's dog for a few days.

One thing I found particularly troubling was the frequent depiction of Robert Downey, Jr. using drugs. No one else in the theatre seemed to react to this, but I surely can't be the only one that remembers that, before his recent comeback, Downey was most famous for his crippling drug problems. I'm glad that things have turned around for him, since he is a fantastic actor and deserves the recognition he is now receiving. But seeing him tossing handfuls of Vicodin into his mouth left an awful pit in my stomach. Was the line, "I've never done drugs in my life," intended to be ironic? I know a film should be able to view its character as separate from the performer, but I still found this troubling. Maybe viewed ten years from now the film wouldn't have this same effect, but it wasn't that long ago that the most famous image of Downey was not in an iron suit but in an orange jump suit.

Another thing that bugged me was how the many scene-stealing actors in the supporting cast were so underused. Juliette Lewis, Danny McBride, and RZA are great, but their appearances are basically reduced to cameos, and they could have been utilized so much more. (The last time I saw RZA on film was in Funny People last year, where he wore a goofy deli worker's uniform. Here he's in a security guards uniform. What is it that's so funny about seeing the RZA in uniform? The appeal is weirdly strong).

These flaws aside, the movie is still hilarious and clever. Like I said earlier though, its greatest strength is in its emotional sincerity that is so often absent from Phillips' movies and other comedies like them. It was a refreshing viewing and wasn't at all the Hangover retread I expected. Even though this follows the particular plot formula of a buddy comedy, this movie has another layer to it that sets it apart from the others in the pack.

Saturday, November 6, 2010

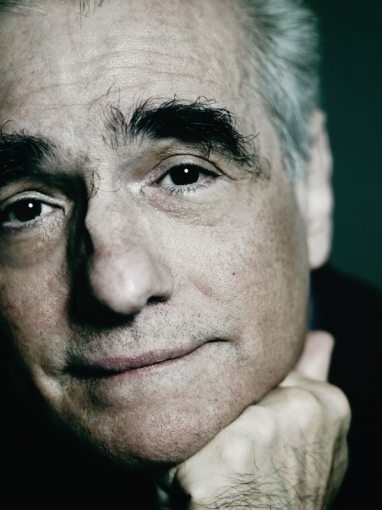

Bring On the Dancing Girls: Who's That Knocking at My Door

While studying film at NYU under professor Haig Manoogian, a young Martin Scorsese penned a planned trilogy of semi-autobiographical screenplays that chronicled the coming of age of a young Italian-American man growing up in New York's lower east side. The first script, titled Jerusalem, Jerusalem, followed the central character as a teenager studying in a seminary to become a priest. The second, Bring On the Dancing Girls, dealt with the conflict between his Catholic views and sexual realities. And the third, Season of the Witch, depicted his initiation into the lower echelons of the mafia in Little Italy.

Bring On the Dancing Girls began production as a short student film at NYU, eventually expanding into a feature, Scorsese's first. It was originally screened with the title I Call First at the Chicago Film Fest in 1967, but it was theatrically released with the title Who's That Knocking at My Door in 1969.

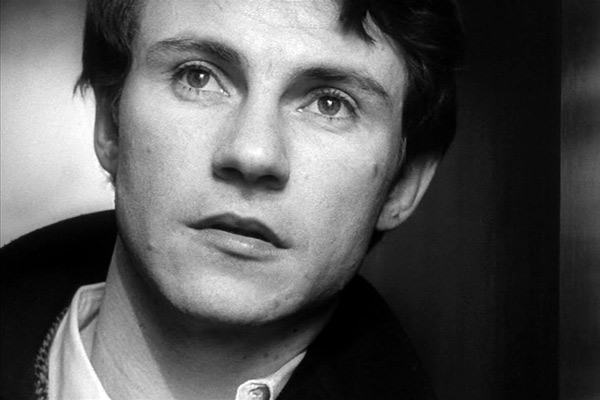

The film deals with Catholic guilt perhaps more explicitly than any of Scorsese's subsequent features. The young protagonist, J.R (Harvey Keitel in his first film role)., is a typical young guy living in New York's Little Italy, spending his weekend nights cruising around with his group of friends, killing time by drinking, shooting the shit, seeing movies, trying to get laid. He's young, smart, and hopelessly bored.

A strong sense of everyday, mundane boredom pervades the film. We get the strong sense that J.R.'s nights out with his friends are painfully routine, and that he has perhaps lived the same night many nights over. This makes it all the more important when J.R. meets a beautiful, unnamed young woman (Zina Bethune) on the ferry. The two make a connection in their conversations about John Wayne movies. The two begin seeing each other and J.R. falls desperately in love.

The extend of J.R.'s affection is apparent in his treatment of "the girl" as compared to how he and his friends treat other women in their sexual exploits. In one scene at a party, him and his friends interact with two girls whom they have never met before. The girls have clearly been invited to the party for the purpose of sex, and nothing else. J.R. and his friends view the women as sexual objects, present only to be used to fulfill the desires of the young men.

By comparison, J.R. views Bethune's character as an almost angelic figure. He idealizes her to an extreme degree and places her on a pedestal high above all other girls. He declines to engage in sexual activity with her, which he so readily pursues with other girls he does not hold in the same esteem.

It is through these relationships that J.R.'s skewed views on sex and on women become clear. The forbidden, Catholic view of sex that has been drilled into J.R. manifests itself intensely in these interactions. He views sex as a sin, and women who practice it are therefore tainted. J.R. can never view the girls at the party as women worthy of his affection. They are, through their sins, lesser than him. On the other hand, Bethune's character is an unreachable goddess. J.R. can't bring himself to make love to her because, by doing so, he will taint her through her own sexuality.

On paper, the problems of this sexist viewpoint are apparent. However, these problems manifest themselves for J.R. when "the girl" confesses to him that she is not a virgin; she was raped by the last boy she was romantically involved with. J.R.'s view of her is instantly poisoned with this news, and he walks away from the conversation, unable to cope.

It is at this point that the issues of conflict and guilt truly begin to plague J.R. He is able to see how his feelings and beliefs contradict the logic of the situation; he loves the girl, but his image of her that lead him to love her has been destroyed. Although she is logically innocent, she is still theologically impure.

His complex highlights not just the problems of just this particular relationship, but of J.R.'s romantic aspirations as a whole. J.R.'s views result in his complete inability to achieve romantic happiness to any degree; he can never be with a woman he considers below him, but he also can't have any woman he deems worthy, because once he does have her, he himself spoils her.

What makes the film particularly brilliant is that it chooses not to condemn J.R.'s obviously sexist beliefs, but rather forces the audience to identify with them. The film does not condone the beliefs either; it makes it explicitly clear that the girl is not a bad person but a smart, independent, and capable girl who was, tragically, the victim of a brutal crime. J.R., too, is able to see this from a logical standpoint, but is unable to reconcile this logic with his belief system.

The film doesn't demonize or endorse Catholicism or sexism, but rather explores the emotional landscape that results from the conflict between belief and emotion, logic and faith, teaching and experience. It is clear that Scorsese sympathizes with the female character, and sees J.R.'s dismissal of her as repugnant. But this is J.R.'s film, and although the film allows the viewer to pass judgment on the character rather than doing so itself.

In fact, a strong sense of Catholic identity is apparent throughout the film. Catholic imagery can be found in every nook and cranny of this movie. The fantasy sequence in which J.R. is tied to the bed makes Keitel look uncannily like a crucified Christ. Religious icons fill J.R.'s home, and we get the sense that, even when he is not explicitly dealing with religion, his religious identity manifests itself in every aspect of his life. The film's final scene, in which J.R. cuts his lip on a crucifix while kissing it, is a perfect piece of symbolism that illustrates the double-edged sword of J.R.'s religious identity, and how his church brings him both peace and pain.

Watching the film, one intrinsically gets the feeling that Scorsese truly understands this material. This film is the first example of dozens by Scorsese that deal with Catholic guilt, and the inability to reconcile one's Catholic beliefs and lessons with their experience of the world and their feelings towards it. J.R. doesn't think that the girl has done something wrong, but he believes it. The film is not for everyone, but for Scorsese fans and for people interested in the theme of Catholic guilt, or of dogma versus human experience, this film is a fantastically dark moral labyrinth.

An Ordinary Parish Priest: The Scorsese Filmography

Over this past summer, I undertook the somewhat daunting task of viewing the entire feature filmography of my favourite living director, Martin Scorsese. I viewed the films chronologically by release date, and did this purely for my own enjoyment. I had been inspired to look at all the films after picking up a copy of Roger Ebert's fantastic book, Scorsese by Ebert. Being obsessed with movies, the thorough analysis that Ebert provided of Scorsese's career didn't quench the thirst I had for insight on Scorsese's works. Instead, it merely served as a jumping-off point for my curiosity about the great director, and I was compelled to watch all his films and do some writing of my own.

So, basically, I'm going to write a series of blog entries about his features. I'll probably post them in the order in which the films were released, although I might deviate. Also, I'll obviously post about other subjects, I'm not interested in just blogging about Marty.

Sadly, due to their absence from rental stores at the time of my binge, I was unable to view Kundun, his 1997 film about the Dalai Lama, or his 2008 Rolling Stones concert film, Shine a Light. However, hopefully I will have had the opportunity to view them by the time I reach them in his filmography. I might also write about some of his shorts or his documentary work, depending on how I'm feeling.

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

The Social Network: Humanity Versus Genius

As the year is nearing its end, I find myself giving in to that irresistible urge to start creating lists and naming the "best" films or records of the year. I know this is a silly undertaking, but then again, so are the Oscars, and I still find myself getting excited for them every year. Even though there's still a solid two months left in 2010 and there is still plenty of time for contenders to come out, I still find myself going over the films I've seen over the last ten months trying to find which ones stand out above the rest. Time and time again, I find myself drifting back towards David Fincher's The Social Network.

What I find so particularly intriguing about Fincher's film isn't the detailed outline of the founding of Facebook as a business entity (brilliantly scripted by The West Wing creator Aaron Sorkin), or even the supposed checkered past of the social networking website (the movie asserts that not only was the website spawned from a drunken act of misogyny, but also that the basic framework of the site was a stolen idea). What intrigues me most about The Social Network is its commentary on the nature of genius, and how that genius comes both as an asset and a crippling handicap.

The character of Mark Zuckerberg, played to perfection by Jesse Eisenberg, is one of the most intriguing movie anti-heroes in recent memory, and the more I dwell on him, the more I feel inclined to include him with Travis Bickle, Daniel Plainview, and Charles Foster Kane on the list of all-time great subjects of brilliant character pieces in film. Although the character Mark Zuckerberg probably bears little resemblance to the real Mark Zuckerberg, the character himself is far more interesting and fertile for analysis. Many will probably see The Social Network more as a social commentary or a sort of pseudo-historical film rather than a character piece. The film is all of these things, but its greatest strength lies in the character of Mark and the double-edged sword of his genius.

Although the film makes no attempt to make Mark seem likable or relatable, there is no question about the fact that the film certainly regards him as a genius. We see his natural inclination to computer programming, and it becomes clear that although he is not the most well-known or well-loved on the Harvard campus, his technical wizardry is unparalleled. Mark things and breathes in code. When he his dumped by his girlfriend, his retaliation doesn't come in words or physical actions, but in HTML.

However, the careful viewer will see that, in order for Mark to gain this upper hand in his mental capacity for programming, he also has to lose something. Mark's superior understanding of computer language comes at the cost of his ability to connect with anyone on a human level. His obsession with computer coding, and eventually with Facebook, send him into a sort of mental tunnel vision that make him cold towards other people, unable to relate or empathize with anyone else. The film is rife with examples of this: the first thing we see is Mark being dumped by his girlfriend, and we can hardly blame her. His prickish and insensitive personality is apparent from his first lines. Throughout the movie, Mark betrays and manipulates business partners, friends, and allies left and right, but he doesn't seem to do these things out of mean spirit or even selfishness. On the contrary, when Mark is confronted by those he has wronged, he usually seems unable to understand why they are angry with him.

Mark's shortcoming comes from this inability to understand other people; in order to understand computer language so thoroughly, his understanding of humanity is sacrificed. This is evident not just in his interpersonal relationships, but in his social relationships as a whole. Mark desperately wants to be accepted into one of the Harvard final clubs or fraternities, but despite his intelligence, he remains a nobody. His failure to do so manifests itself as a deep resentment of the system that rejected him. His creation of Facebook, and the many "fuck yous" he throws out along the way, seem to be retaliation towards the entire social world that has rejected him. However, his longing to join this world persists despite his projected hatred; when his best friend Eduardo is accepted to an exclusive final club, Mark's jealousy is clear. When Eduardo claims that Mark betrayed him just to get back at him for making it into the final club, there isn't much to make the audience think that this isn't the case.

The film doesn't even seem to regard Mark as entirely human; we see many times throughout the film that he seems to be impervious to the cold, and when other characters are painfully freezing, he doesn't even seem to notice the temperature. He walks through thick snow in casual clothing and doesn't seem to notice. He rejects food every time he is offered it, and we almost never see him eating, save for at the end of the film when we see a sliver of humanity peak through as he connects with a young law intern played by the always wonderful Rashida Jones. The things that most people are sensitive to, Mark is unable to recognize, and these physical oddities serve to symbolize his emotional ones.

And therein lies the brilliance of The Social Network's depiction of the dual nature of genius. Mark longs to become a part of the social in-crowd, but despite all his success, never succeeds in doing so, not because he won't, but because he can't. The handicap of his genius, despite opening seemingly infinite doors for him, will never open the only door he wants to go through. The financial and commercial successes he achieves do not satisfy his loneliness, as we see at the end of the film as he gazes longingly at his ex's Facebook profile. He wants nothing more than to be accepted, and when he finds he is incapable of achieving this, he strikes back with a relentless ambition that drives him to zealotry and near madness.

We see how the other characters fall victim to emotional plights as they climb the ladder of success. Eduardo is torn apart by his rocky relationships with his best friend and insane girlfriend, and Sean Parker (in a surprisingly effective performance by Justin Timberlake) spirals into a lifestyle of sex and drug abuse, but Mark never falls victim to the vices of their world, because he can never be a part of it.

In his review of The Social Network, Roger Ebert wisely compares the character of Mark Zuckerberg to the real life figure of Bobby Fischer. Their similarities are uncanny: Fischer, a childhood chess prodigy who was arguably the greatest player that ever lived, found himself a victim of his own inability to apply to human connection the same virtuosic touch he applied to the game of chess. Fischer became increasingly bizarre, openly speaking about his belief in conspiracy theories that the Jewish people were a secret evil organization that controlled the world (Fischer was himself Jewish), and he died an exile in Scandinavia, a sad genius ignored by his home country as a shadow of what he once was. His brilliance gave way to an arrogance that was both his greatest success and his undoing, much like Mark Zuckerberg.

It is sometimes theorized that genius itself is not an increased mental capacity in an individual, but rather a slightly skewed perspective from which the subject views the world. This is certainly the case with Mark Zuckerberg, who is able to see the world through the eyes of a computer but not through the eyes of a human being. It is in the exploration of Mark's genius that the film finds its own genius.

What I find so particularly intriguing about Fincher's film isn't the detailed outline of the founding of Facebook as a business entity (brilliantly scripted by The West Wing creator Aaron Sorkin), or even the supposed checkered past of the social networking website (the movie asserts that not only was the website spawned from a drunken act of misogyny, but also that the basic framework of the site was a stolen idea). What intrigues me most about The Social Network is its commentary on the nature of genius, and how that genius comes both as an asset and a crippling handicap.

The character of Mark Zuckerberg, played to perfection by Jesse Eisenberg, is one of the most intriguing movie anti-heroes in recent memory, and the more I dwell on him, the more I feel inclined to include him with Travis Bickle, Daniel Plainview, and Charles Foster Kane on the list of all-time great subjects of brilliant character pieces in film. Although the character Mark Zuckerberg probably bears little resemblance to the real Mark Zuckerberg, the character himself is far more interesting and fertile for analysis. Many will probably see The Social Network more as a social commentary or a sort of pseudo-historical film rather than a character piece. The film is all of these things, but its greatest strength lies in the character of Mark and the double-edged sword of his genius.

Although the film makes no attempt to make Mark seem likable or relatable, there is no question about the fact that the film certainly regards him as a genius. We see his natural inclination to computer programming, and it becomes clear that although he is not the most well-known or well-loved on the Harvard campus, his technical wizardry is unparalleled. Mark things and breathes in code. When he his dumped by his girlfriend, his retaliation doesn't come in words or physical actions, but in HTML.

However, the careful viewer will see that, in order for Mark to gain this upper hand in his mental capacity for programming, he also has to lose something. Mark's superior understanding of computer language comes at the cost of his ability to connect with anyone on a human level. His obsession with computer coding, and eventually with Facebook, send him into a sort of mental tunnel vision that make him cold towards other people, unable to relate or empathize with anyone else. The film is rife with examples of this: the first thing we see is Mark being dumped by his girlfriend, and we can hardly blame her. His prickish and insensitive personality is apparent from his first lines. Throughout the movie, Mark betrays and manipulates business partners, friends, and allies left and right, but he doesn't seem to do these things out of mean spirit or even selfishness. On the contrary, when Mark is confronted by those he has wronged, he usually seems unable to understand why they are angry with him.

Mark's shortcoming comes from this inability to understand other people; in order to understand computer language so thoroughly, his understanding of humanity is sacrificed. This is evident not just in his interpersonal relationships, but in his social relationships as a whole. Mark desperately wants to be accepted into one of the Harvard final clubs or fraternities, but despite his intelligence, he remains a nobody. His failure to do so manifests itself as a deep resentment of the system that rejected him. His creation of Facebook, and the many "fuck yous" he throws out along the way, seem to be retaliation towards the entire social world that has rejected him. However, his longing to join this world persists despite his projected hatred; when his best friend Eduardo is accepted to an exclusive final club, Mark's jealousy is clear. When Eduardo claims that Mark betrayed him just to get back at him for making it into the final club, there isn't much to make the audience think that this isn't the case.

The film doesn't even seem to regard Mark as entirely human; we see many times throughout the film that he seems to be impervious to the cold, and when other characters are painfully freezing, he doesn't even seem to notice the temperature. He walks through thick snow in casual clothing and doesn't seem to notice. He rejects food every time he is offered it, and we almost never see him eating, save for at the end of the film when we see a sliver of humanity peak through as he connects with a young law intern played by the always wonderful Rashida Jones. The things that most people are sensitive to, Mark is unable to recognize, and these physical oddities serve to symbolize his emotional ones.

And therein lies the brilliance of The Social Network's depiction of the dual nature of genius. Mark longs to become a part of the social in-crowd, but despite all his success, never succeeds in doing so, not because he won't, but because he can't. The handicap of his genius, despite opening seemingly infinite doors for him, will never open the only door he wants to go through. The financial and commercial successes he achieves do not satisfy his loneliness, as we see at the end of the film as he gazes longingly at his ex's Facebook profile. He wants nothing more than to be accepted, and when he finds he is incapable of achieving this, he strikes back with a relentless ambition that drives him to zealotry and near madness.

We see how the other characters fall victim to emotional plights as they climb the ladder of success. Eduardo is torn apart by his rocky relationships with his best friend and insane girlfriend, and Sean Parker (in a surprisingly effective performance by Justin Timberlake) spirals into a lifestyle of sex and drug abuse, but Mark never falls victim to the vices of their world, because he can never be a part of it.

In his review of The Social Network, Roger Ebert wisely compares the character of Mark Zuckerberg to the real life figure of Bobby Fischer. Their similarities are uncanny: Fischer, a childhood chess prodigy who was arguably the greatest player that ever lived, found himself a victim of his own inability to apply to human connection the same virtuosic touch he applied to the game of chess. Fischer became increasingly bizarre, openly speaking about his belief in conspiracy theories that the Jewish people were a secret evil organization that controlled the world (Fischer was himself Jewish), and he died an exile in Scandinavia, a sad genius ignored by his home country as a shadow of what he once was. His brilliance gave way to an arrogance that was both his greatest success and his undoing, much like Mark Zuckerberg.

It is sometimes theorized that genius itself is not an increased mental capacity in an individual, but rather a slightly skewed perspective from which the subject views the world. This is certainly the case with Mark Zuckerberg, who is able to see the world through the eyes of a computer but not through the eyes of a human being. It is in the exploration of Mark's genius that the film finds its own genius.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)